Since the dawn of the quantum era, perhaps no question has loomed larger in the minds of theoretical physicists than just what, exactly, the nature of reality is. Are quantum objects real, with well-defined positions and momenta, even in the absence of an observation or measurement to determine them? Out of all the ways to interpret quantum mechanics — from parallel universes to a collapsing wavefunction to theories of hidden variables — we still don’t have any evidence that favors one interpretation over another. All we’ve been able to do, even as of 2026, is rule out certain deterministic interpretations that cannot be consistent with the experiments we’ve actually performed.

Nevertheless, despite how slow progress has been in uncovering the full nature of our quantum reality, humanity has taken many important steps since the founding of quantum mechanics. We’ve uncovered the deeper science of quantum field theory, understanding that not just the particles that compose reality but that even the underlying fields have a quantum nature. Bell’s theorem and Bell’s inequality have opened up whole new classes of quantum experiments to probe the behavior of our quantum Universe. The cloning of quantum states has been disproven. Local, real, hidden variable interpretations have been ruled out, and Nobel Prizes have been awarded for advances in quantum foundations, for quantum tunneling, and for improving our understanding of entanglement.

But here in the 21st century, one advance stands out above all the rest: the Pusey-Barrett-Rudolph (PBR) theorem. Although it hasn’t received a lot of fanfare, it was proven back in 2012 and remains the most important quantum advance of this new century. Here’s what it teaches us about reality.

In quantum physics — at least, to the best of our current knowledge — there are a great many physical scenarios you can set up where even if you know absolutely everything that’s knowable about:

- how the system is set up, including the initial conditions of every particle and the boundary conditions of the system itself,

- and what the laws of physics are that govern the system, including all of the fundamental laws and interactions between every particle and field that exists in the system,

you still won’t be able to determine what’s going to happen and when. The best you’ll be able to do is come up with a set of probabilities for each possible outcome, which is extremely limited in its predictive power.

Have a radioactive atom? You can know what its half-life is, but whether this particular atom decays after a tenth of a half-life, two-thirds of a half-life, one half-life, 2.5 half-lives, six half-lives, or 23 half-lives is something you can’t know in advance; you can only watch the atom and determine when it does actually decay.

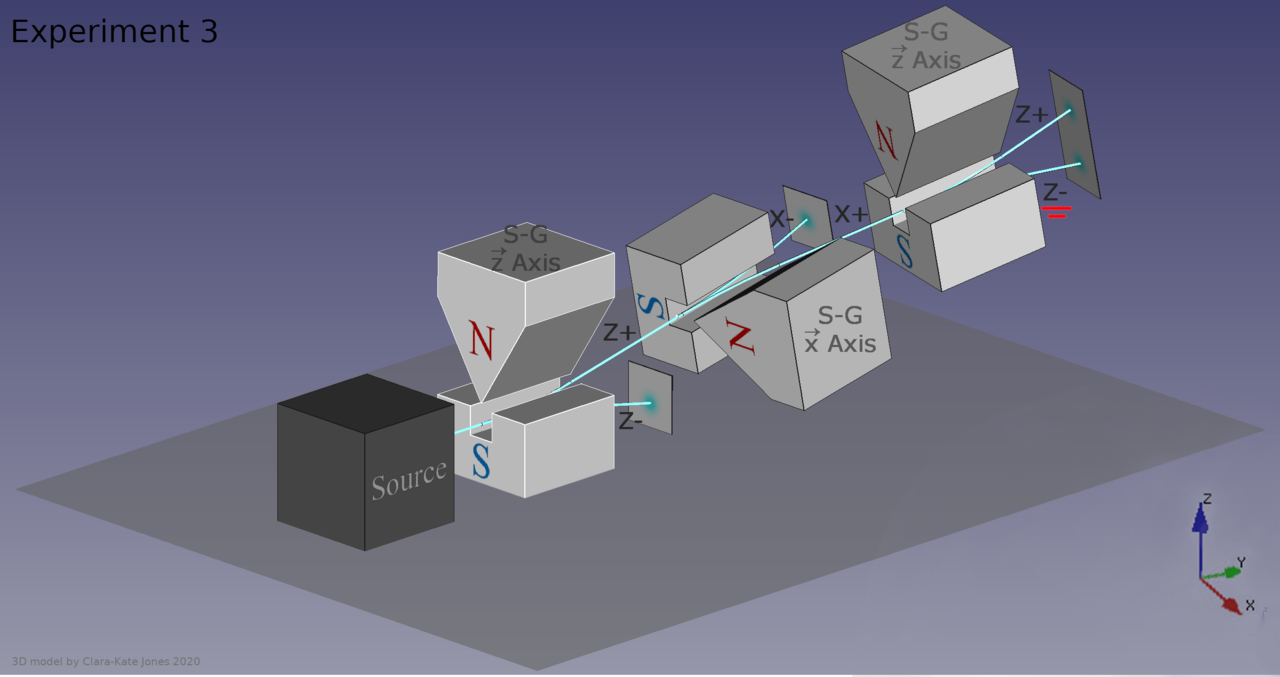

The situation is similar if you want to know where an electron passed through a double slit will arrive on a screen behind it, or which direction a spin-½ particle will deflect in an upward-directed magnetic field. You can calculate the probability of a set of outcomes, but quantum physics gives us no way to determine what the outcome of any one particular quantum system will actually be, no matter how much you know about it.

This fact about the Universe has spawned much outrage among physicists and philosophers alike since it was first noticed, which in turn has led to many proposed scenarios to attempt to resolve the feeling of discomfort that we feel when we encounter and ponder these properties.

- One idea, put forth by Bohr and known as the Copenhagen interpretation, is that reality is fundamentally indeterminate until a measurement or observation is made, where a measurement or observation is defined as an energetic enough interaction with another particle that either reveals knowledge about the system’s state or compels the system into a different state.

- Another idea, the ensemble interpretation, is that reality is fundamentally indeterminate and exists as an ensemble of all possible solution states, and that quantum physics can tell you the probability of outcomes for an infinite ensemble of identically prepared systems. It’s the measurement or observation that then “picks out” which state it’s actually in.

- Still another idea is the many-worlds interpretation, which asserts that the wavefunction, each time it’s not in a single, well-determined quantum state, creates and expands into a series of parallel universes, and that only when a measurement occurs is “our Universe’s path” chosen, leaving the others behind as alternative timelines in the multiverse which don’t interact with our own.

- And finally, there are collections of interpretations that insist that reality, as a fundamental level, truly is deterministic, even if we cannot identify or measure the variables that determine those outcomes, and that there are instead “hidden variables” that underlie the system and do 100% determine what outcomes will occur.

This last idea is part of a wide collection of “hidden variable theories” or interpretations of quantum mechanics where even if we ourselves can’t determine what’s going to occur, all of the events that ever have occurred or ever will occur are preordained. It’s sort of like imagining you have a vibrating plate with grains of sand atop it, and that you can only measure the individual grains of sand but you can’t observe or measure the plate or its vibrations. To you, it would appear that the grains of sand fluctuate wildly and at random, but it’s merely a manifestation of classical chaos; if you could see, measure, and understand the physics of the plate, you would find that this was in fact just a complex, deterministic system.

Einstein favored the notion of hidden variables, arguing in his famous 1935 paper (with Nathan Rosen and Boris Podolsky) that quantum mechanics is an incomplete theory, and that finding these hidden variables would complete it. Modern adherents to determinism include pilot wave theory (often known as Bohmian mechanics or de Broglie-Bohm theory), the aforementioned many-worlds interpretation, or the more recent suggestion of superdeterminism.

However, issues about the nature of reality are never, ever decided by our preferences, our ideologies, or our intuition. They are decided by what’s provable and predictable from a theoretical perspective, and then what’s determined to be consistent (or inconsistent) with reality from an experimental, measurable, observable perspective.

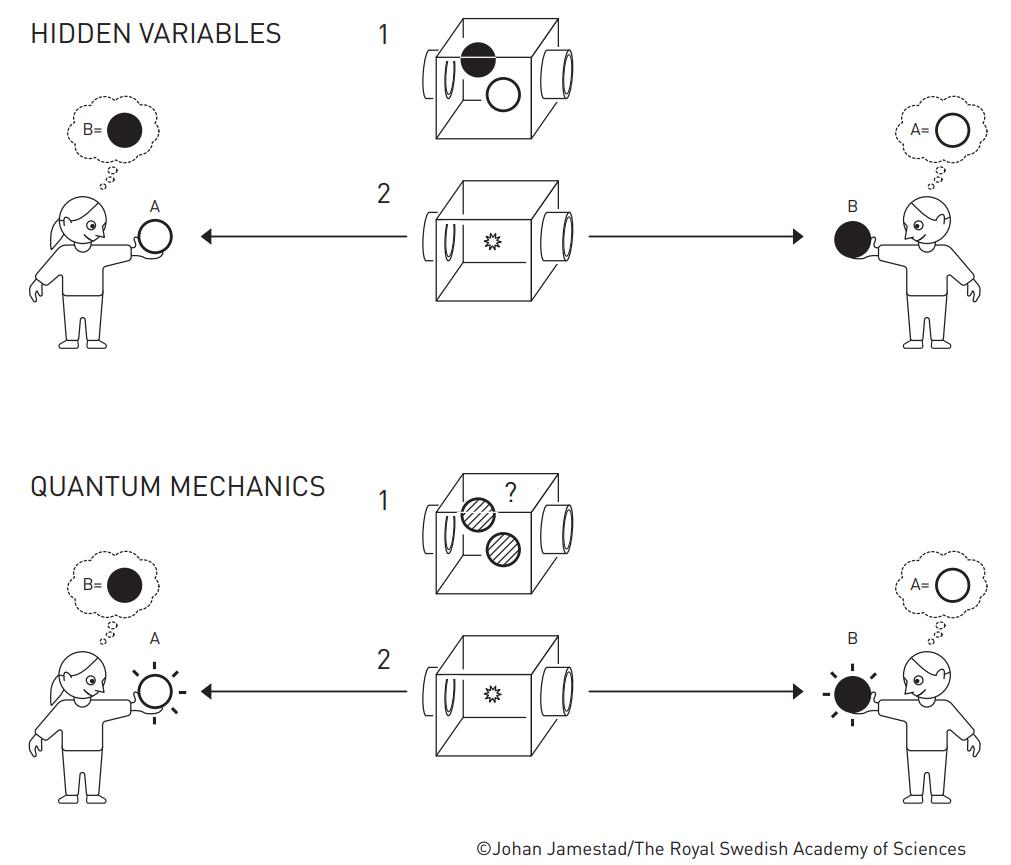

The first meaningful step toward this came in 1964, when physicist John Stewart Bell came up with a collection of theorems and inequalities that allowed the first meaningful, experimental constraints on local (where no signals travel faster-than-light) hidden variable theories. The early tests of Bell’s theorem, as well as extensions to it, were sufficient to rule out or constrain a number of local hidden variable interpretations of quantum mechanics, and that was what the 2022 Nobel Prize in physics — awarded to Alain Aspect, John Clauser, and Anton Zeilinger — was all about.

However, there are always loopholes in any theorem, and one potential way to “get away with” having hidden variables is to have them be non-local: where things happening in one location can affect things happening in another region not via a signal exchanged at or below the speed of light, but at speeds exceeding it, even up to the maximum speed of instantaneously. Contained in these non-local hidden variable theories are the hopes of everyone who seeks to make deterministic sense of the quantum Universe, and the hope that somewhere, somehow, there’s a way to extract more information about reality and what outcomes will occur than standard, conventional quantum mechanics permits.

In classical mechanics, after all, there’s no role that the observer plays in determining the outcome of an observation. What happens would have happened the exact same way whether you were there to see it or not.

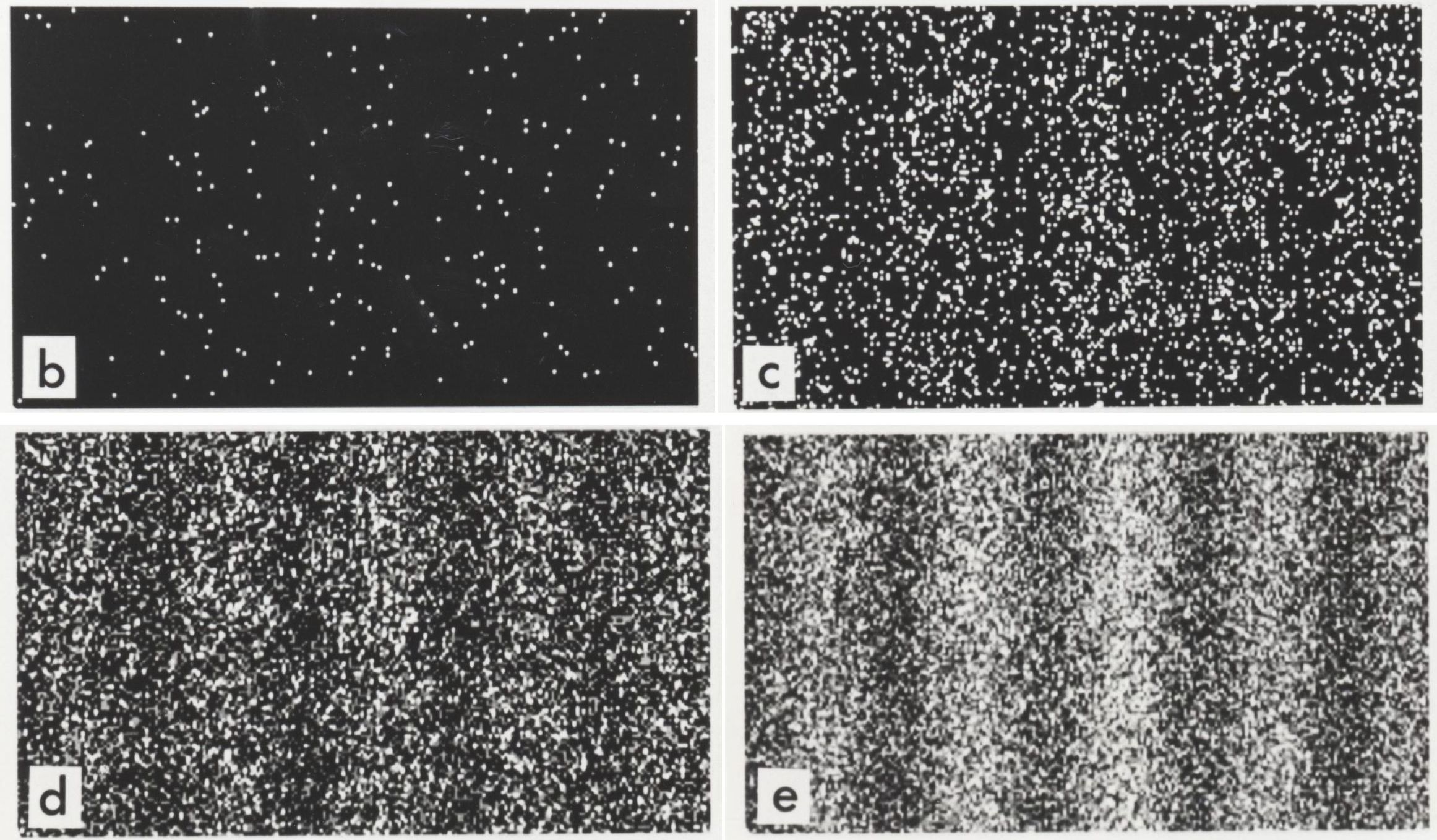

But in quantum mechanics, we know this isn’t the case in a variety of ways. For example, there’s the double slit experiment. If you pass a series of particles (like electrons) or waves (like light) through a double slit, you won’t get, as an outcome, two piles that correspond to things that went through slit #1 and things that went through slit #2. Instead, you’ll get an interference pattern: a hallmark of the quantum wavefunction.

If you reduce the series of particles or waves to individual quanta — electrons sent one at a time or photons sent one at a time through the double slit — you still get the interference pattern. However, if you measure “which slit does each quantum go through,” you can indeed make that measurement, but the act of making it destroys the interference pattern and leads to you seeing the “two piles” option instead. It seems as though nature really does behave differently whether you watch it or not, where “watching” or “making an observation” involves an interaction with another, sufficiently energetic particle to determine the quantum state of the particle passing through the slits.

That’s what physicists often wonder: is there a way to extract more information about the quantum state of any system — and hence, to know more about the potential outcome that will occur — than standard quantum mechanics provides? Are there, at some level, even if we can’t see or measure them, hidden variables? The argument still rages today. Fifteen years ago, a paper came out proving that no extension of quantum theory can have improved predictive power over the predictions of standard quantum mechanics, but then another paper came out arguing that they indeed found loopholes, and potentially testable counterexamples, to that proof.

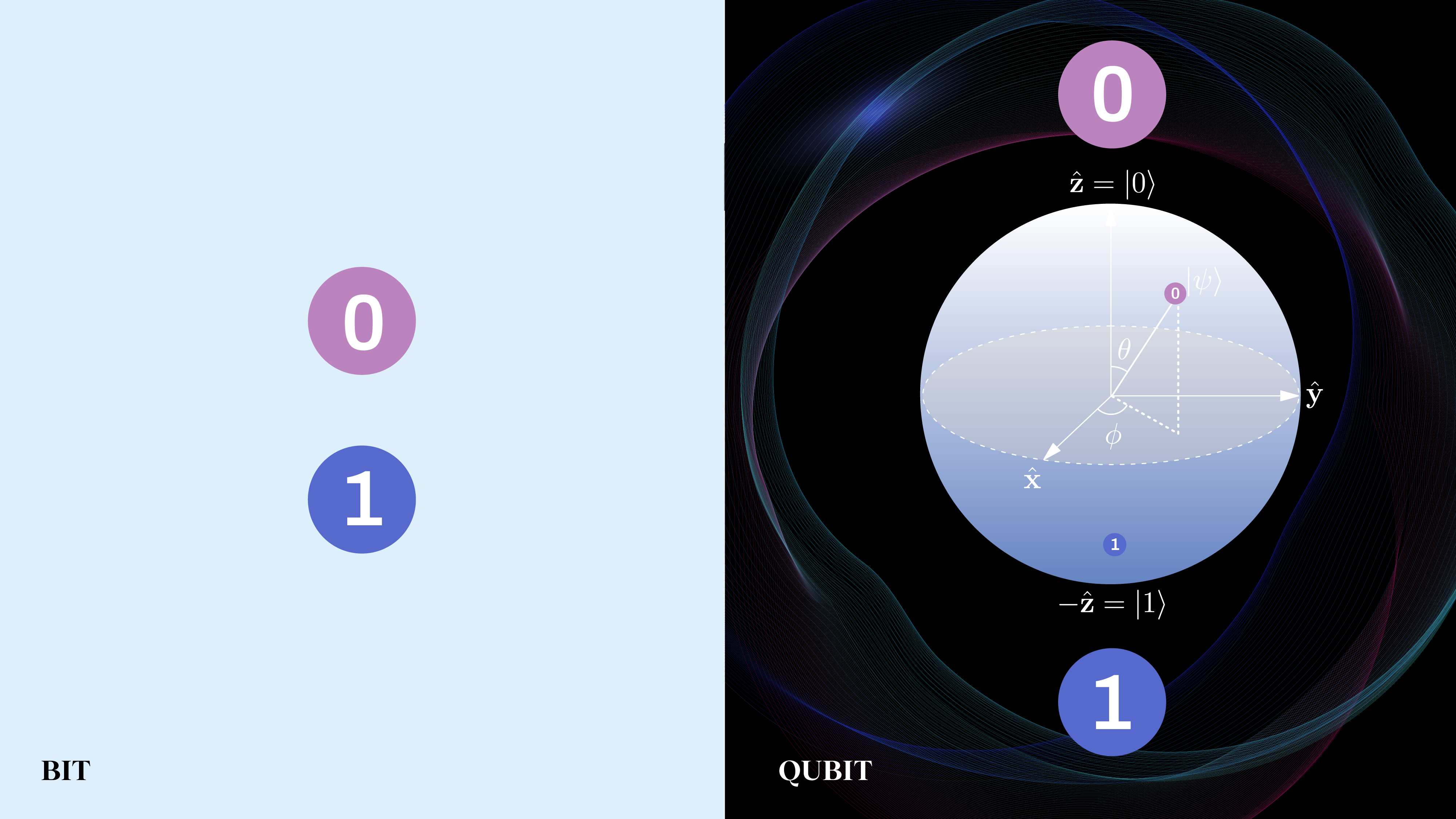

At the core of the argument is whether quantum states are “ontic” or “epistemic” in nature. These aren’t common terms that people use (even most physicists rarely use them), with the difference being as follows.

- For ontic quantum states, those states would correspond directly to states of reality, with no room for additional knowledge about reality existing in some hidden, but unknown to humans, set of information-carrying variables.

- Meanwhile, for epistemic quantum states, those states may correspond only to probabilistic states of knowledge about reality, but those states are allowed to be incomplete, where additional knowledge could exist in some type of hidden, information carrying variables.

With this background in mind, we come to the Pusey-Barrett-Randolph (PBR) theorem, put forth in a paper in 2012.

So, what does a quantum state represent? Is the state a physical property of a quantum system, the same way “position” or “momentum” is a physical property of a classical (non-quantum) system? Or is the quantum state only a statistical/probabilistic property, the same way that the temperature of a gas is a statistical property of a classical system, where the physics can tell you the mean speed of all of the particles and how those speeds are distributed, but cannot tell you anything meaningful about the actual speed of any one individual particle?

That’s what’s at stake if we can determine whether the quantum state is ontic, in which case there is no “hidden” information that could be gleaned if you somehow knew more than what quantum mechanics provides, or epistemic, where just as (classical) particles do have well-defined speeds, the actual quantum state could have underlying properties that are indeed better-informed than we are from quantum mechanics.

The theorem begins, as all good theorems do, from a set of assumptions.

- Quantum systems (like atoms, electrons, and photons) exist, and have at least some physical properties.

- And that either the quantum state encodes everything there is that’s knowable about the system (the ontic approach) or that it merely encodes what an experimenter can know about a system’s properties (the epistemic approach).

These assumptions are generally not seriously debated, as observations and experiments are extraordinarily consistent with all of them.

They then proceed by imagining there are two different methods of preparing a quantum system: method 1, which leads to one quantum state, and method 2, which leads to a second quantum state that is not identical to the first quantum state. Because of the first assumption, after state preparation, these two quantum systems then have some physical properties. Whether those properties are completely described by quantum physics, or whether they’re only completely described by some other, yet undiscovered theory is irrelevant; only that they exist. Whatever those physical properties are, it’s possible to make a complete list of them, at least from a mathematical point of view. Then depending on how reality works, two options arise.

- If the quantum state is ontic, then if you specify the full list of physical properties, you uniquely determine the quantum state.

- On the other hand, if the quantum state is epistemic, then fully specifying the full list of physical properties might not uniquely determine the quantum state; there may be multiple compatible options.

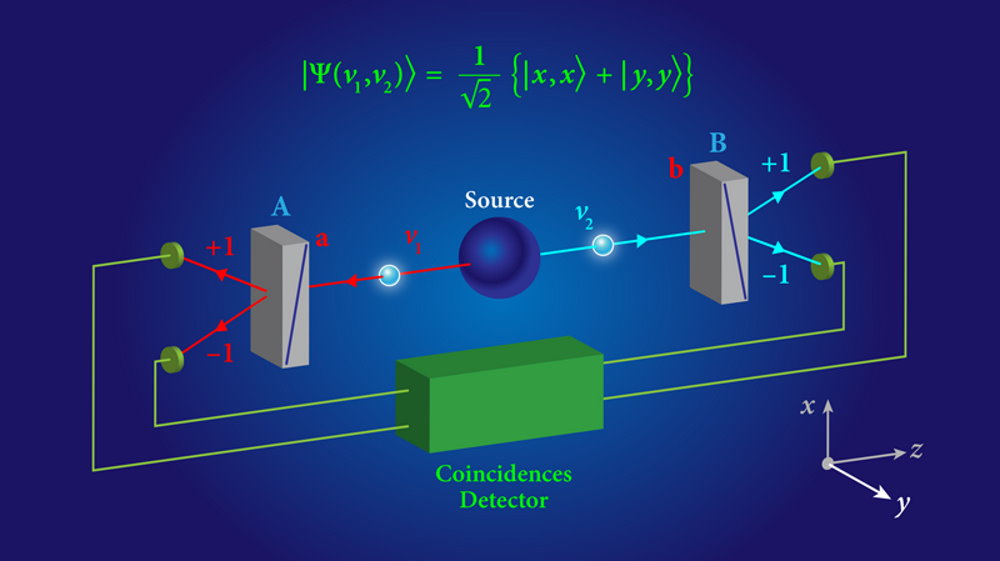

Then imagine that you prepare two quantum systems independently, and that each one’s quantum state is determined by the preparation method. The outcome of the measurement may then only depend on the physical properties of the two systems at the time they are measured.

What Pusey, Barrett, and Rudolph then showed is that unless the quantum state is ontic in nature, the measuring device is sometimes uncertain which preparation method was used. But because the quantum state is determined by the preparation method, it runs the risk of giving an outcome that quantum theory demands must have 0 probability: it cannot occur. And therefore, there is no physical state that can be compatible with both “method 1” and “method 2” simultaneously.

If you then apply this same argument to any pairs of quantum states that arise from preparing two quantum systems made of identical particles in two different ways, then you can uniquely infer the quantum state from the observed physical states. The quantum state is therefore a physical property of the system, and the statistical/epistemic view is demonstrated to be false.

This has enormously profound consequences. It implies that the phenomenon known as “quantum collapse” or “wavefunction collapse” must correspond to a real, physical process, even one that occurs simultaneously between entangled particles separated by large distances: in a non-local fashion. However, if there is no collapse of the quantum state (as in many deterministic interpretations), then each measurable component of the quantum state must have a direct counterpart in reality: undermining the very idea of “hidden variables that determine reality” inherent to the epistemic point of view!

What’s remarkable about this theorem is that it relies solely on three base assumptions made by the authors:

- That if an isolated (non-entangled) quantum system can be prepared with a pure state, there will be a well-defined set of physical properties resulting from that preparation.

- That multiple quantum systems can be independently prepared such that their physical properties are uncorrelated with one another.

- And that measuring apparatuses respond solely to the physical properties of the systems that they are measuring, whether or not those properties are well-determined or obey a probability distribution.

If any of these assumptions are violated or invalidated, then there’s still wiggle room to argue that the quantum state is not a real object, or that quantum systems don’t have any physical properties at all. However, if all three of these assumptions are accepted, then the epistemic interpretation of reality is ruled out, leaving us with no alternative but to accept the “weirdness” of quantum mechanics as inherent to, and fundamental to, the nature of reality. That truly is profound, and why the PBR theorem stands tall as the most important development in quantum foundations of the 21st century so far!

This article The most important quantum advance of the 21st century is featured on Big Think.